Proposed legislation would strip Kentucky’s authority to regulate waterways that fall outside the federal definition for “navigable waters.”

Senate Bill 89 would eliminate existing state protections for groundwater allowing polluters to dump their waste without oversight from the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet. It would also make it more difficult to regulate ephemeral streams in Kentucky.

The legislation is sponsored by Sen. Scott Madon, a first-term Republican from Pineville replacing former Sen. Johnny Turner, who died shortly before the election last November.

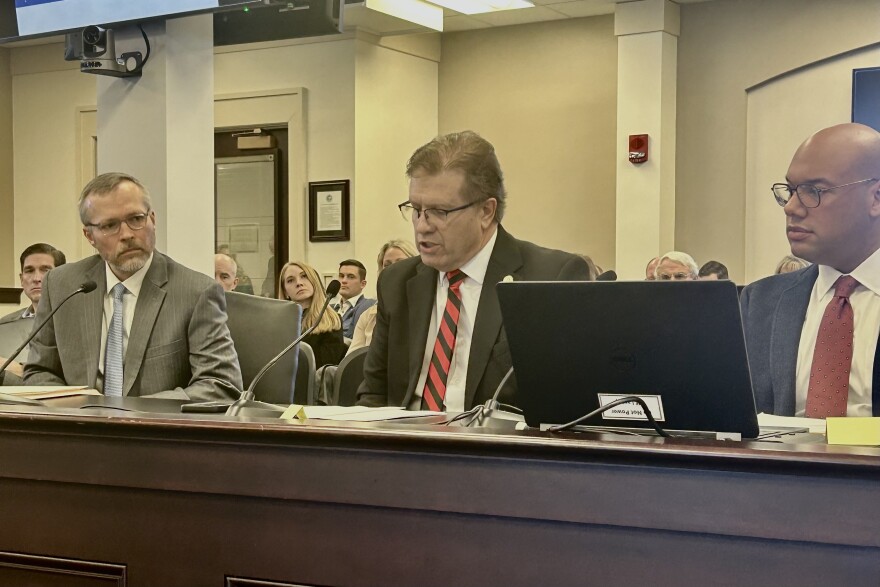

Madon was joined as he presented his bill to the Senate committee by two representatives of the Kentucky Coal Association. He discussed the benefits he believes limiting state pollution regulations would confer on coal companies by eliminating “delays and unnecessary red tape.”

“One of the reasons I ran for office was to protect our coal miners, our coal communities, and to do everything that I possibly can to burn coal for as long as possible, despite the federal government trying to shut us down,” Madon said.

The measure passed a Senate committee Wednesday and will now head to the Senate floor.

The term “navigable waters” has become a political football kicked back and forth between Republican and Democrat presidential administrations, with the latter expanding the definition to further protect habitats like wetlands, and the former contracting the definition in hopes of slashing regulations and spurring economic development.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the 2023 case Sackett v. EPA that wetlands that aren’t connected above ground to another body of water, isn’t included in the term “navigable waters.” It excludes bodies of water that aren’t regularly flowing or permanent and, according to activists, may not include groundwater.

Who are my lawmakers?

We do not store your information.

Kentucky’s own definition is broader than the federal one, and includes essentially all bodies of surface and underground water, including reservoirs and marshes. But Madon says statute should have already aligned state and federal laws. The Kentucky statute Madon referenced blocks the environment cabinet from enforcing certain standards higher than federal ones for permits under the Clean Water Act.

“No doubt, Senate Bill 89 protects the coal industry from these unwarranted and some may say, unlawful practices by the Energy and Environmental cabinet,” Madon said. “As you all know, coal is the most reliable and affordable energy resource we have.”

More than a dozen coal-fired power plants in Kentucky have polluted groundwater with arsenic, lead, mercury and other hazardous metals found in coal ash, according to an analysis of industry data from environmental advocates Earthjustice and the Environmental Integrity Project.

Executives for several utilities, including those in Kentucky, are now asking the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to roll back regulations designed to mitigate coal ash pollution in groundwater.

With Wednesday’s hearing running long, a committee member moved to cut off the comment period in the middle of environmental advocates offering their opposition to the bill and stopping lawmakers from asking further questions.

Audrey Ernstberger with the Kentucky Resources Council said Kentucky’s natural topography includes sinkholes, extensive caves and underground water systems. She said that means there are times when the cabinet should be enforcing controls of limits on properties because they are contaminating something downstream — even if it doesn’t look like a traditional body of surface water.

“When the water disappears and becomes an underground stream, all of a sudden, the cabinet [would] lose authority to then issue a permit for someone who wants to discharge,” Ernstberger said.

The current definition of Kentucky’s water or “waters of the Commonwealth” was put in place in a 1973 law. By the 1990s, 80% of the state’s original wetlands were removed, according to the University of Kentucky, during land management activities and partly due to highway construction and coal mining.

“The intent, as I understand it, of the original legislation, was taking the full spectrum of water that exists in our state, and making a concerted effort and decision to protect it in all of its forms here in the state,” Ernstberger said.

State government and politics reporting is supported in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.