This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

*This story contains discussions of sexual assault and the abuse and deaths of children*

It was around 3:30 a.m. and most of the other residents at the Home of the Innocents were still sleeping. But the 12-year-old girl couldn’t wait until morning to tell an adult the truth about what just happened.

She had been through this before. By the time she was 8 years old, she had already suffered tremendous sexual trauma. According to a state report, she was trafficked by her family and taken into state custody. For the last nine months, she had been living at the residential care facility in Louisville that specializes in treating children with significant behavioral needs.

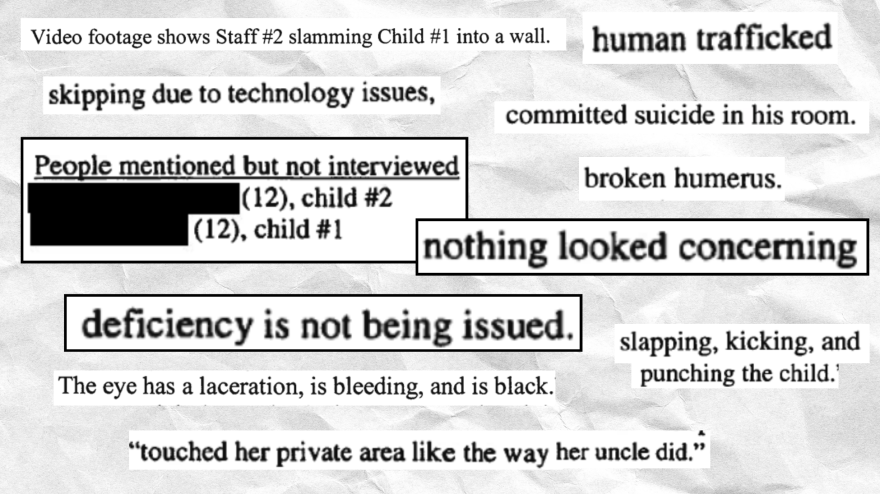

The staff already knew something went awry: that another resident, a 12-year-old boy, was caught standing over her bed. The staff member conducting bed checks said that both children were clothed, and the boy was sent back to his room. Their conclusion was that nothing was amiss. But the girl said that wasn’t true. The boy broke in while she was sleeping, she said, and “touched her private area like the way her uncle did.”

The facility was charged with keeping her safe, and the state was charged with holding that facility accountable. She said she’d been harmed. But her word wouldn’t be enough.

The Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting reviewed two and a half years of investigations into reports of abuse or neglect by children in state custody, housed in Louisville’s residential care homes. What we found is an investigative process characterized by poor communication, riddled with incomplete details and encumbered by a deep reliance on the facilities under investigation. The system that promises to monitor these facilities and protect children from abuse often devalues the child’s perspective of what happened — communicating to them time and time again that they are untrustworthy and unbelievable.

“It is very, very, very rare that children are disclosing abuse that has not happened,” said Shannon Moody, chief policy and strategy officer with Kentucky Youth Advocates, a nonprofit that advocates and lobbies for policies to protect youth. “And we need to believe them.”

When the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services learned of the girl’s allegation in April 2020, the Office of Inspector General’s Division of Regulated Child Care (DRCC) opened an investigation. The agency is responsible for licensing residential care facilities and investigating possible rule violations. A state worker interviewed staff members and reviewed video footage that showed the boy steal the girl’s room key when a staff member wasn’t looking, and use it to go into her room. He was there for eight minutes, outside the view of cameras. The state worker also learned the boy had a history of sexually acting out, and made sexual threats to staff on a regular basis.

A Home of the Innocents spokesperson told KyCIR that they couldn’t discuss the specifics of this case, but said that they routinely report incidents to the state and cooperate with their investigations.

“We take every reported injury, and every rare, but tragic, incident to heart,” they said in an email. “We are always searching for anything we can do to prevent harm.”

Even though the boy was able to steal a key and enter another child’s bedroom — a threat to her safety — the facility didn’t face any disciplinary action. In the investigator’s report, alongside documentation of the extensive sexual abuse the girl had suffered, they quoted staff in saying she “has a history of lying” and that she often “exhibits inappropriate sexual behaviors and allegations.” The state closed the case a month later without ever speaking to the girl.

Text:Jasmine Demers Interactive element:Justin Hicks

Her experience is common. We reviewed hundreds of pages of records from 130 investigations conducted by the DRCC between January 2020 and July 2023, which involved allegations of physical, sexual and verbal abuse as well as neglect and inadequate supervision.

The majority of these investigations were closed and labeled unsubstantiated, with no violations cited. The reports show that more than 70% of the unsubstantiated cases came down to one thing — a child’s word versus staff members’ word. And without video footage or another person corroborating the child’s allegation, the investigator sided against the child nearly every single time.

In over half of the unsubstantiated cases, the child who made the allegation was never even interviewed. State rules and best practices dictate that children should be interviewed whenever possible, unless it would cause them extensive emotional harm.

“I don't know how you would be able to make a finding, whether it's substantiated or not, without talking to the child in the situation,” Moody said.

Cabinet for Health and Family Services Secretary Eric Friedlander said in an interview with KyCIR that workers investigating complaints are doing the best they can. He disputed the premise that unsubstantiated cases meant children weren’t being believed.

“Unsubstantiated just means we don’t have enough evidence to substantiate,” he said. “It doesn’t mean we don’t believe people. I think there's more gray there than black and white.”

But Friedlander acknowledged that the lack of interviews with affected children overall, and the failure to speak to the girl at the Home of the Innocents in particular, raise concerns.

“I do wish we would have talked to her and heard her,” Friedlander said.

A complicated and compromised investigative process

The state sends children to residential care homes when they need more intensive behavioral or psychological treatment than they could get in a foster home, if one were even available. Often, they’re disconnected from families, without someone on the outside advocating for their care. If children are harmed in these facilities, they’re reliant on the state government to investigate and level accountability.

One of the most recent examples of this involved the death of a 7-year-old boy at the Brooklawn residential care facility in Louisville last year.

Ja’Ceon Terry was just 4 years old when he was taken into state custody. He had been severely neglected for most of his childhood and had witnessed drug use, domestic violence and prostitution in his home. He cycled through several foster homes, residential care facilities and psychiatric hospitals before being admitted to Brooklawn in June 2022.

Five weeks later, he was held down by two staff members until he lost consciousness and died.

KyCIR previously reported about the state’s investigation into his death, which showed that in his final hours of life, Ja’Ceon was publicly shamed, verbally abused and left in his room alone for nearly six hours before the hold that led to his death.

The state investigation into his death uncovered six more concerning incidents at the facility that should have been reported. Several involved serious injuries, and in one instance, investigators found that a child was punched and kicked by a staff member. Brooklawn officials told KyCIR that they couldn’t comment on specific cases, but that they take every incident seriously.

The state health cabinet stopped placing children at the facility and permanently revoked the license for Brooklawn’s psychiatric division, where Ja’Ceon was admitted. They resumed foster placements at the facility’s other programs in May.

Child welfare experts say there’s an inherent risk in confirming cases of abuse — the state needs these facilities.

Roughly 500 youth in state custody are living in 48 residential homes across the state at any given time – about 6% of all the state’s children in an out-of-home placement.

Though the facilities can privately admit children, their state contracts account for most of their admissions – and research from Kentucky Youth Advocates shows that the state relies on them, too. The state says they’ve continued to see a decline in the number of foster families willing to accept kids for placement, especially those with acute mental and behavioral problems. Residential facilities are sometimes the only option when state officials can’t find a family member or a foster home willing to take a child.

This can pose a major conflict of interest. Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, which advocates against the use of group living facilities, said these relationships complicate finding and substantiating abuse.

“When the state is investigating abuse in a foster home or a group home, they are investigating themselves because they put the child there,” he said. “So that creates an enormous incentive to see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil and write no evil in the case file.”

He said if the state were to believe the child, they would have to actually do something about it. They might have to find new placements for every child who was abused or mistreated at these facilities, which they often do not have the capacity to do.

Friedlander, the state cabinet secretary overseeing these investigations, says the agency that regulates residential care facilities — the DRCC — is independent and doesn’t have to deal with the pressure of child placements.

But Moody said she doesn’t see how they could remain unbiased.

“How thorough of an investigation can you do if your supervisors, your boss, your oversight is coming from the larger cabinet that is also responsible for the contracts and a lot of the provisions of services for the situations that are being investigated?” she asked.

The ties are undeniably closer in investigations run by the Department for Community Based Services (DCBS), the division which investigates alleged abuse by individuals. Friedlander agrees that there’s an objectivity problem in DCBS investigations, since the same agency investigates abuse and decides where kids are placed.

“We're referring [children] to a facility, and then we're going out and investigating that same facility,” Friedlander said. “It's not that I think anybody does anything wrong. I think when you get a relationship with folks that you work with all the time, you can have a blind spot.”

The cabinet has already started to make some changes, he said. In January, they moved investigations of reports of abuse in residential care from small regional teams to one statewide team.

“Outcomes are now more consistent and there is less chance of bias,” a cabinet spokesperson said in an email.

But Wexler says the DRCC investigations done by the independent arm of the state agency are vulnerable to bias, too. When they have to discipline, suspend or even shut down a residential care center, it could create an even larger backlog of children waiting for new placements.

In fact, when Ja’Ceon Terry was killed at Brooklawn and the state stopped placing children at the facility, they started to see an increase in the number of children who were waiting for placement with nowhere to go. The cabinet said during a legislative meeting in July that nearly 90 kids had to stay in state offices or hotels throughout the year.

“They have a tremendous incentive to ignore abuse,” Wexler said. “And that shows utter contempt for the young people they are supposedly there to help."

Kicks, slaps, punches, but no findings

Shaelynn Cain cycled through several residential care facilities in Louisville by the time she was 18.

She was first taken into state custody when she was just 9 years old after being abused and neglected by her family. Now 23, Cain said her time in residential care was traumatic. She remembers getting upset and being restrained by staff members several times as a child and teenager.

“One time, I was in a hold where I couldn’t breathe. I was face down and they were on top of me,” she said. “They've got all their body weight on you in full force. They put their knees in your back. And it hurts.”

But she never reported it to anyone. She was sure it wouldn’t matter.

“It’s our word against theirs,” Cain said.

Even when incidents like this are reported, they often go unsubstantiated. The majority of investigations reviewed by KyCIR involved a physical management issue by staff – nearly 60 cases over two and a half years where children alleged they were placed in an unsafe restraint or were kicked, slapped, punched or choked by a staff member.

Kentucky regulation says that physical restraint may only be used if a child’s behavior poses imminent danger of physical harm to themselves or others. When they are used correctly, they help to immobilize and keep the child safe during a crisis.

In 41 of those cases, state officials found no violations.

At Brooklawn in April 2021, one report said a 14-year-old had been upset throughout the day and that he was “making verbal threats to hit staff.” After being placed in multiple holds by three staff members, he was taken to the hospital, where an X-ray showed his arm was broken. The state worker investigating the incident determined the injury was unintentional.

In another case in December 2021, a 12-year-old at Home of the Innocents said that a staff member slapped him in the face and slammed him against the wall of his bedroom. The staff member denied the allegation and wrote in the incident report that the boy attempted to hit him, so he put him in a restraint. The same staff member had two previous suspensions for improper physical management. An investigator closed the case two months later, marking it unsubstantiated because there was no evidence to confirm what the boy said.

Shannon Moody of Kentucky Youth Advocates, who has worked in residential care, said that holds are unfortunately needed to keep some kids from hurting themselves or others. But she said they still happen way too often, and they are difficult to regulate in the moment.

“The reality is that you can go through training as many times as you want,” she said. “But you're doing a training in a room that is calm, relaxed, collegial, you're learning with your peers, and it's not a tense situation. It's never going to feel like it actually does when you're in that situation.”

Video evidence important, but inconsistent

When state investigators confirmed allegations, it was almost always because video evidence backed up a child’s story.

Out of the 130 cases we reviewed, less than a third had video footage available. But it wasn’t always usable. In some of the cases, the footage was unclear or grainy or involved a camera with technology issues.

In March 2020, a 12-year-old girl at Home of the Innocents said a staff member kicked her in the stomach, punched her in the shoulder and pushed her. The report said no other staff members witnessed the incident, but someone said that they heard screaming coming from the common area. When the state worker asked to review the video footage, they were told by staff that “their camera systems are jumping 20 seconds ahead and because of that, the only footage is before and after the incident.” Without hard evidence to back up the girl’s claim, the state closed the case — no violations. Home of the Innocents declined to discuss the specifics of the case.

When staff members decide to place a child in a physical hold, policy dictates that they do it in the view of cameras. But video evidence wasn’t always available, even when it should have been. In 60% of the cases where a physical management issue was alleged, video footage was not available because the hold was performed in private areas. None of the facilities were cited for violating the policy.

In November 2020, for example, a 16-year-old was at Maryhurst for less than 10 days when she said she was held down on her bed for 10 minutes by staff, and that she couldn’t breathe. The state’s report said the hold started after the girl swung a toilet seat at a staff member, but there was no video footage to confirm what happened. They never talked to the girl, who was discharged and sent to a psychiatric hospital the day after the incident.

Staff told the state worker that the hold was performed correctly, and that no one heard her say she couldn’t breathe. Case closed — no violations.

Officials at Maryhurst declined to comment on this specific case.

Cases closed without talking to kids

When video footage is not available, investigators have to rely solely on interviews with staff and children. But in more than half of the cases we reviewed, the child involved was never interviewed.

We also found dozens of cases where the child was discharged from the facility and relocated – some to foster homes, others to a different facility – before the state even started their investigation. The files show no indication that the workers tried to contact the child once they were moved.

In one case, a 15-year-old at Home of the Innocents said that a staff member grabbed her neck during a hold. Video footage didn’t offer a clear view of the incident and the staff member denied the allegation. The child was discharged 10 days before the state started its investigation, and they never spoke to her.

At the Bellewood residential care center, another boy said he was choked and thrown to the floor. The facility’s incident report said the boy was exhibiting “dangerous behavior” and tried to kick a staff member, but there was no video inside his bedroom. The 13-year-old was discharged by the time the state investigated and they never interviewed him. When they spoke to the accused staff member, she denied the allegation. Bellewood officials said they could not comment on specific cases.

Both cases were closed — no violations.

Failure to communicate

When something happens to a child at a facility, a DCBS social worker is supposed to ensure that all other agencies have been informed of the incident — including their colleagues at the Office of Inspector General’s Division of Regulated Child Care (DRCC), which investigates the facility violations. Whenever possible, the agencies should be conducting a combined investigation and sharing information about their findings and the facility’s history.

But this doesn’t always happen.

In one report from October 2022, a 9-year-old boy said that a staff member at Home of the Innocents had “inappropriately touched him” – not just a policy violation but a potential crime.

When the DRCC launched a state investigation to determine if the facility violated policies, the investigator learned that the accused staff member had already resigned from the facility. Then, two days later, he asked to be added to the boy’s approved contact list – and his request was granted, meaning he could call, visit and even bring the boy to his private residence. The records do not indicate whether the former staff members' access to the child was revoked during the investigation.

Since this involved a sexual assault allegation against a facility worker, DCBS was required to initiate a forensic interview, conducted by specially trained professionals at a child advocacy center with the goal of obtaining a statement from a child in an objective and legal setting. But the investigator running the parallel investigation for the DRCC couldn’t get any information about that interview from DCBS – even though both agencies are housed under the same cabinet of state government.

KyCIR was denied access to detailed records from DCBS. But in the DRCC report, the investigator noted that a forensic interview had not been completed, and that they still had no information about it after contacting five different DCBS workers multiple times over the course of three months.

By January 2023, over a year after the child had moved to a foster home, the forensic interview had still not been completed and the child had not been spoken to. The last communication the investigator received from DCBS said “It does not appear that the investigation has been written up, no documentation.” The DRCC closed its investigation the following month — no violations.

‘Who pays for this?’

The failings of the system meant to keep kids in state custody safe are upsetting, but not surprising to those close to the issue.

Tamara Vest spent several months in residential foster care in Lexington when she was a teenager.

“I still have the effects of it every single day,” she said. “I deal with depression and anxiety from the trauma of being moved around and all of the things that I dealt with in these facilities.”

She said the cases of abuse that are reported probably don’t even come close to what is actually happening to kids at these facilities. She remembers trying to speak up about the neglect she experienced there, but she felt like no one cared.

“They just told me, ‘Well nobody else wants you. You can't go back home,’” she said. “I felt emotionally unsafe.”

After she graduated from college, Vest went to work as a social worker for the Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Although she didn’t have a good experience in foster care, she thought she could help make a difference for other kids. But the system works against social workers too, she said — they’re underpaid and forced to to take on unmanageable caseloads.

“There were just a lot of red flags for me,” she said. “I knew that just wasn't the place for me to make change.”

Now she serves as a policy and advocacy analyst for Kentucky Youth Advocates and is working on getting her clinical social work license. A survey conducted by Kentucky Youth Advocates last year showed that many youth living in residential care facilities across the state had shared experiences — reporting physical, sexual and verbal abuse that only compounded the impact of their past trauma.

Their research points to a need for more family-based and less restrictive placements. They want residential care facilities to be transformed into centers for family well-being, providing opportunities for family therapy, supervised visitation and wraparound services that work to reunite children with their loved ones.

Shannon Moody says the state needs to reduce the number of kids going into residential care as a whole. These facilities are largely underfunded and don’t have enough staff who are qualified to handle the needs of the kids who live there — and that makes them inherently risky places for young people to be.

“I'm not saying there is no need for residential care, because in certain circumstances there are,” she said. “But the reality is, as soon as kids enter residential, they are at a higher risk of being victimized further, of having their mental health issues exacerbated by not being supported, by not having connection to family, by being more isolated.”

Facilities also need stricter performance measures, she said. If they’re not producing good outcomes for kids, they should lose their contract.

In response to KyCIR’s findings, Sen. Whitney Westerfield, a Republican from Fruit Hill, said something has to change.

Westerfield, a member of the senate’s families and children committee, said investigations need more independence, and investigators need to start listening to the children who report abuse. If it were up to him, he’d erase the entire flowchart for the state's Cabinet for Health and Family Services and start all over to ignite a “culture change.”

The cabinet, he said, is the state’s biggest with the most money flowing through it. But he called it a “bureaucratic blackhole of a mess.”

For proof, he points to KyCIR’s findings.

“And who pays for this?” he asked. “The children whose cases don't get looked at and the children whose cases get looked at and then ignored.”

Lily Burris contributed reporting.

Support for this story was provided in part by the Jewish Heritage Fund.